Quadratic Payments: A Primer

2019 Dec 07

See all posts

Quadratic Payments: A Primer

Special thanks to Karl Floersch and Jinglan Wang for

feedback

If you follow applied mechanism design or decentralized governance at

all, you may have recently heard one of a few buzzwords: quadratic

voting, quadratic

funding and quadratic

attention purchase. These ideas have been gaining popularity rapidly

over the last few years, and small-scale tests have already been

deployed: the Taiwanese

presidential hackathon used quadratic voting to vote on winning

projects, Gitcoin Grants used

quadratic funding to fund public goods in the Ethereum ecosystem,

and the Colorado Democratic party also

experimented with quadratic voting to determine their party

platform.

To the proponents of these voting schemes, this is not just another

slight improvement to what exists. Rather, it's an initial foray into a

fundamentally new class of social technology which, has the potential to

overturn how we make many public decisions, large and small. The

ultimate effect of these schemes rolled out in their full form could

be as deeply transformative as the industrial-era advent of mostly-free

markets and constitutional democracy. But now, you may be thinking:

"These are large promises. What do these new governance technologies

have that justifies such claims?"

Private goods, private

markets...

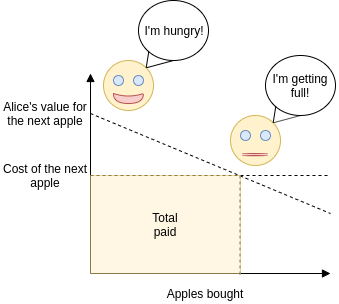

To understand what is going on, let us first consider an existing

social technology: money, and property rights - the invisible social

technology that generally hides behind money. Money and private property

are extremely powerful social technologies, for all the reasons

classical economists have been stating for over a hundred years. If Bob

is producing apples, and Alice wants to buy apples, we can economically

model the interaction between the two, and the results seem to make

sense:

Alice keeps buying apples until the marginal value of the next apple

to her is less than the cost of producing it, which is pretty much

exactly the optimal thing that could happen. This is all formalized in

results such as the "fundamental

theorems of welfare economics". Now, those of you who have learned

some economics may be screaming, but what about imperfect

competition? Asymmetric

information? Economic

inequality? Public goods? Externalities? Many

activities in the real world, including those that are key to the

progress of human civilization, benefit (or harm) many people in

complicated ways. These activities and the consequences that arise from

them often cannot be neatly decomposed into sequences of distinct trades

between two parties.

But since when do we expect a single package of technologies to solve

every problem anyway? "What about oceans?" isn't an argument against

cars, it's an argument against car maximalism, the

position that we need cars and nothing else. Much like how private

property and markets deal with private goods, can we try to use economic

means to deduce what kind of social technologies would work well for

encouraging production of the public goods that we need?

... Public goods, public markets

Private goods (eg. apples) and public goods (eg. public parks, air

quality, scientific research, this article...) are different in some key

ways. When we are talking about private goods, production for multiple

people (eg. the same farmer makes apples for both Alice and Bob) can be

decomposed into (i) the farmer making some apples for Alice, and (ii)

the farmer making some other apples for Bob. If Alice wants apples but

Bob does not, then the farmer makes Alice's apples, collects payment

from Alice, and leaves Bob alone. Even complex collaborations (the "I, Pencil" essay popular

in libertarian circles comes to mind) can be decomposed into a series of

such interactions. When we are talking about public goods, however,

this kind of decomposition is not possible. When I write this

blog article, it can be read by both Alice and Bob (and everyone else).

I could put it behind a paywall, but if it's popular enough it

will inevitably get mirrored on third-party sites, and paywalls are in

any case annoying and not very effective. Furthermore, making an article

available to ten people is not ten times cheaper than making the article

available to a hundred people; rather, the cost is exactly the

same. So I either produce the article for everyone, or I do not

produce it for anyone at all.

So here comes the challenge: how do we aggregate together people's

preferences? Some private and public goods are worth producing, others

are not. In the case of private goods, the question is easy, because we

can just decompose it into a series of decisions for each individual.

Whatever amount each person is willing to pay for, that much gets

produced for them; the economics is not especially complex. In the case

of public goods, however, you cannot "decompose", and so we need to add

up people's preferences in a different way.

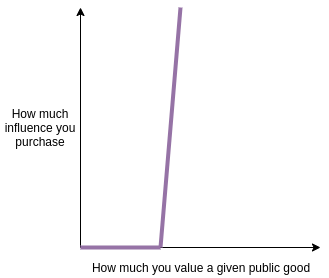

First of all, let's see what happens if we just put up a plain old

regular market: I offer to write an article as long as at least $1000 of

money gets donated to me (fun fact: I

literally did this back in 2011). Every dollar donated increases the

probability that the goal will be reached and the article will be

published; let us call this "marginal probability" p. At a

cost of $k, you can increase the probability that the

article will be published by k * p (though eventually the

gains will decrease as the probability approaches 100%). Let's say to

you personally, the article being published is worth $V.

Would you donate? Well, donating a dollar increases the probability it

will be published by p, and so gives you an expected

$p * V of value. If p * V > 1, you donate,

and quite a lot, and if p * V < 1 you don't donate at

all.

Phrased less mathematically, either you value the article enough

(and/or are rich enough) to pay, and if that's the case it's in your

interest to keep paying (and influencing) quite a lot, or you don't

value the article enough and you contribute nothing. Hence, the only

blog articles that get published would be articles where some single

person is willing to basically pay for it

themselves (in my experiment in 2011, this prediction was

experimentally verified: in most

rounds,

over half of the total contribution came from a single donor).

Note that this reasoning applies for any kind of mechanism that

involves "buying influence" over matters of public concern. This

includes paying for public goods, shareholder voting in corporations,

public advertising, bribing politicians, and much more. The little guy

has too little influence (not quite zero, because in the real world

things like altruism exist) and the big guy has too much. If you had an

intuition that markets work great for buying apples, but money is

corrupting in "the public sphere", this is basically a simplified

mathematical model that shows why.

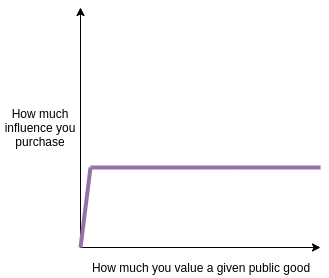

We can also consider a different mechanism: one-person-one-vote.

Let's say you can either vote that I deserve a reward for writing this

article, or you can vote that I don't, and my reward is proportional to

the number of votes in my favor. We can interpret this as follows: your

first "contribution" costs only a small amount of effort, so you'll

support an article if you care about it enough, but after that point

there is no more room to contribute further; your second contribution

"costs" infinity.

Now, you might notice that neither of the graphs above look quite

right. The first graph over-privileges people who care a lot

(or are wealthy), the second graph over-privileges people who care

only a little, which is also a problem. The single sheep's desire

to live is more important than the two wolves' desire to have a tasty

dinner.

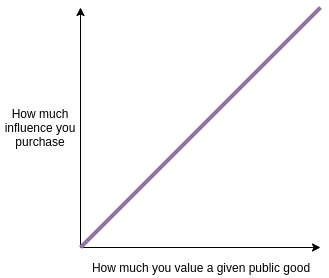

But what do we actually want? Ultimately, we want a scheme where

how much influence you "buy" is proportional to how much you

care. In the mathematical lingo above, we want your k

to be proportional to your V. But here's the problem: your

V determines how much you're willing to pay for

one unit of influence. If Alice were willing to pay $100 for

the article if she had to fund it herself, then she would be willing to

pay $1 for an increased 1% chance it will get written, and if Bob were

only willing to pay $50 for the article then he would only be willing to

pay $0.5 for the same "unit of influence".

So how do we match these two up? The answer is clever: your n'th

unit of influence costs you $n . That is, for example, you could

buy your first vote for $0.01, but then your second would cost $0.02,

your third $0.03, and so forth. Suppose you were Alice in the example

above; in such a system she would keep buying units of influence until

the cost of the next one got to $1, so she would buy 100 units. Bob

would similarly buy until the cost got to $0.5, so he would buy 50

units. Alice's 2x higher valuation turned into 2x more units of

influence purchased.

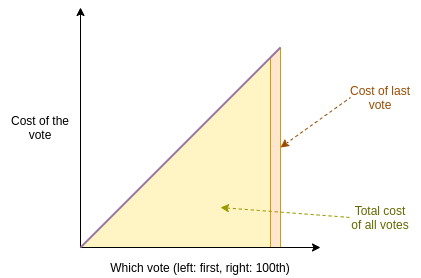

Let's draw this as a graph:

Now let's look at all three beside each other:

Notice that only quadratic voting has this nice property that the

amount of influence you purchase is proportional to how much you care;

the other two mechanisms either over-privilege concentrated interests or

over-privilege diffuse interests.

Now, you might ask, where does the quadratic come from?

Well, the marginal cost of the n'th vote is $n (or $0.01 * n),

but the total cost of n votes is \(\approx \frac{n^2}{2}\). You can view this

geometrically as follows:

The total cost is the area of a triangle, and you probably learned in

math class that area is base * height / 2. And since here base and

height are proportionate, that basically means that total cost is

proportional to number of votes squared - hence, "quadratic". But

honestly it's easier to think "your n'th unit of influence costs

$n".

Finally, you might notice that above I've been vague about what "one

unit of influence" actually means. This is deliberate; it can mean

different things in different contexts, and the different "flavors" of

quadratic payments reflect these different perspectives.

Quadratic Voting

See also the original paper: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract%5fid=2003531

Let us begin by exploring the first "flavor" of quadratic payments:

quadratic voting. Imagine that some organization is trying to choose

between two choices for some decision that affects all of its members.

For example, this could be a company or a nonprofit deciding which part

of town to make a new office in, or a government deciding whether or not

to implement some policy, or an internet forum deciding whether or not

its rules should allow discussion of cryptocurrency prices. Within the

context of the organization, the choice made is a public good (or public

bad, depending on whom you talk to): everyone "consumes" the results of

the same decision, they just have different opinions about how much they

like the result.

This seems like a perfect target for quadratic voting. The goal is

that option A gets chosen if in total people like A more, and option B

gets chosen if in total people like B more. With simple voting ("one

person one vote"), the distinction between stronger vs weaker

preferences gets ignored, so on issues where one side is of very high

value to a few people and the other side is of low value to more people,

simple voting is likely to give wrong answers. With a private-goods

market mechanism where people can buy as many votes as they want at the

same price per vote, the individual with the strongest preference (or

the wealthiest) carries everything. Quadratic voting, where you can make

n votes in either direction at a cost of n2, is right in the

middle between these two extremes, and creates the perfect balance.

Note that in the voting case, we're deciding two options, so

different people will favor A over B or B over A; hence, unlike the

graphs we saw earlier that start from zero, here voting and preference

can both be positive or negative (which option is considered positive

and which is negative doesn't matter; the math works out the same

way)

As shown above, because the n'th vote has a cost of n,

the number of votes you make is proportional to how much you value one

unit of influence over the decision (the value of the decision

multiplied by the probability that one vote will tip the result), and

hence proportional to how much you care about A being chosen over B or

vice versa. Hence, we once again have this nice clean "preference

adding" effect.

We can extend quadratic voting in multiple ways. First, we can allow

voting between more than two options. While traditional voting schemes

inevitably fall prey to various kinds of "strategic voting" issues

because of Arrow's

theorem and Duverger's

law, quadratic voting continues

to be optimal in contexts with more than two choices.

The intuitive argument for those interested: suppose

there are established candidates A and B and new candidate C. Some

people favor C > A > B but others C > B > A. in a regular

vote, if both sides think C stands no chance, they decide may as well

vote their preference between A and B, so C gets no votes, and C's

failure becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. In quadratic voting the

former group would vote [A +10, B -10, C +1] and the latter [A -10, B

+10, C +1], so the A and B votes cancel out and C's popularity shines

through.

Second, we can look not just at voting between discrete options, but

also at voting on the setting of a thermostat: anyone can push the

thermostat up or down by 0.01 degrees n times by paying a cost of

n2.

Plot

twist: the side wanting it colder only wins when they convince the other

side that "C" stands for "caliente".

Quadratic funding

See also the original paper: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract%5fid=3243656

Quadratic voting is optimal when you need to make some fixed number

of collective decisions. But one weakness of quadratic voting is that it

doesn't come with a built-in mechanism for deciding what goes on the

ballot in the first place. Proposing votes is potentially a source of

considerable power if not handled with care: a malicious actor in

control of it can repeatedly propose some decision that a majority

weakly approves of and a minority strongly disapproves of, and keep

proposing it until the minority runs out of voting tokens (if you do the

math you'll see that the minority would burn through tokens much faster

than the majority). Let's consider a flavor of quadratic payments that

does not run into this issue, and makes the choice of decisions itself

endogenous (ie. part of the mechanism itself). In this case, the

mechanism is specialized for one particular use case: individual

provision of public goods.

Let us consider an example where someone is looking to produce a

public good (eg. a developer writing an open source software program),

and we want to figure out whether or not this program is worth funding.

But instead of just thinking about one single public good, let's create

a mechanism where anyone can raise funds for what they claim to

be a public good project. Anyone can make a contribution to any project;

a mechanism keeps track of these contributions and then at the end of

some period of time the mechanism calculates a payment to each project.

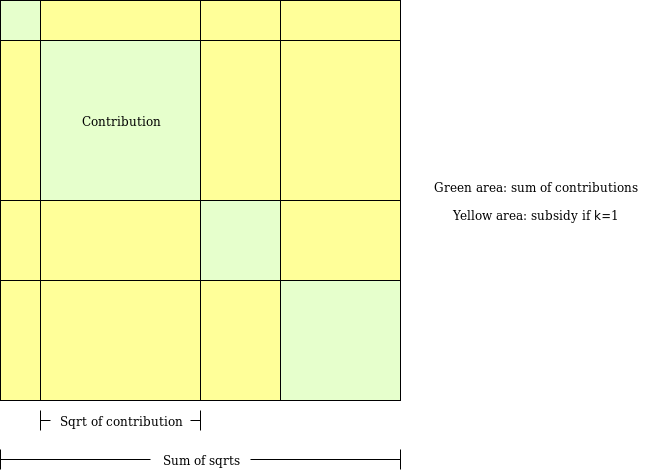

The way that this payment is calculated is as follows: for any given

project, take the square root of each contributor's contribution, add

these values together, and take the square of the result. Or in math

speak:

\[(\sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{c_i})^2\]

If that sounds complicated, here it is graphically:

In any case where there is more than one contributor, the computed

payment is greater than the raw sum of contributions; the difference

comes out of a central subsidy pool (eg. if ten people each donate $1,

then the sum-of-square-roots is $10, and the square of that is $100, so

the subsidy is $90). Note that if the subsidy pool is not big enough to

make the full required payment to every project, we can just divide the

subsidies proportionately by whatever constant makes the totals add up

to the subsidy pool's budget; you can prove that this solves the

tragedy-of-the-commons problem as well as you can with that subsidy

budget.

There are two ways to intuitively interpret this formula. First, one

can look at it through the "fixing market failure" lens, a surgical fix

to the tragedy of

the commons problem. In any situation where Alice contributes to a

project and Bob also contributes to that same project, Alice is making a

contribution to something that is valuable not only to herself, but also

to Bob. When deciding how much to contribute, Alice was only

taking into account the benefit to herself, not Bob, whom she most

likely does not even know. The quadratic funding mechanism adds a

subsidy to compensate for this effect, determining how much Alice "would

have" contributed if she also took into account the benefit her

contribution brings to Bob. Furthermore, we can separately calculate the

subsidy for each pair of people (nb. if there are N people

there are N * (N-1) / 2 pairs), and add up all of these

subsidies together, and give Bob the combined subsidy from all pairs.

And it turns out that this gives exactly the quadratic funding

formula.

Second, one can look at the formula through a quadratic voting lens.

We interpret the quadratic funding as being a special case of

quadratic voting, where the contributors to a project are voting for

that project and there is one imaginary participant voting against it:

the subsidy pool. Every "project" is a motion to take money from the

subsidy pool and give it to that project's creator. Everyone sending

\(c_i\) of funds is making \(\sqrt{c_i}\) votes, so there's a total of

\(\sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{c_i}\) votes in

favor of the motion. To kill the motion, the subsidy pool would need to

make more than \(\sum_{i=1}^n

\sqrt{c_i}\) votes against it, which would cost it more than

\((\sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{c_i})^2\). Hence,

\((\sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{c_i})^2\) is the

maximum transfer from the subsidy pool to the project that the subsidy

pool would not vote to stop.

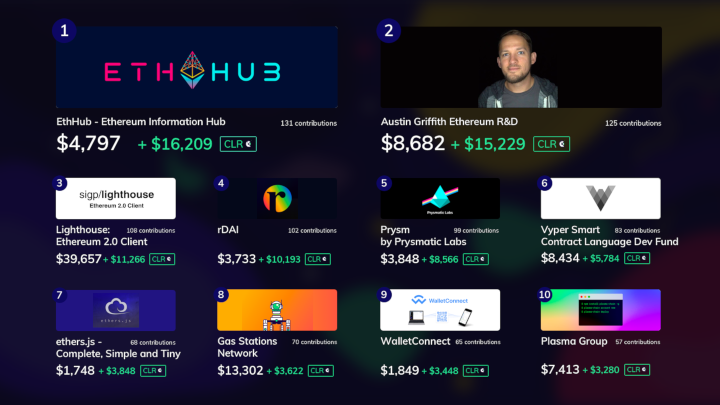

Quadratic funding is starting to be explored as a mechanism for

funding public goods already; Gitcoin grants for funding

public goods in the Ethereum ecosystem is currently the biggest example,

and the most recent round led to results that, in my own view, did a

quite good job of making a fair allocation to support projects that the

community deems valuable.

Numbers

in white are raw contribution totals; numbers in green are the extra

subsidies.

Quadratic attention payments

See also the original post: https://kortina.nyc/essays/speech-is-free-distribution-is-not-a-tax-on-the-purchase-of-human-attention-and-political-power/

One of the defining features of modern capitalism that people love to

hate is ads. Our cities have ads:

Source:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/argonavigo/36657795264

Our subway turnstiles have ads:

Source:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NYC,_subway_ad_on_Prince_St.jpg

Our politics are dominated by ads:

Source:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e3/Billboard_Challenging_the_validity_of_Barack_Obama%27s_Birth_Certificate.JPG

And even the rivers and the skies have

ads. Now, there are some places that seem to not have this

problem:

But really they just have a different kind of ads:

Now, recently there are attempts to move beyond this in

some cities. And on

Twitter. But let's look at the problem systematically and try to see

what's going wrong. The answer is actually surprisingly simple: public

advertising is the evil twin of public goods production. In the case of

public goods production, there is one actor that is taking on an

expenditure to produce some product, and this product benefits a large

number of people. Because these people cannot effectively coordinate to

pay for the public goods by themselves, we get much less public goods

than we need, and the ones we do get are those favored by wealthy actors

or centralized authorities. Here, there is one actor that reaps a large

benefit from forcing other people to look at some image, and

this action harms a large number of people. Because these

people cannot effectively coordinate to buy out the slots for the ads,

we get ads we don't want to see, that are favored by... wealthy actors or

centralized authorities.

So how do we solve this dark mirror image of public goods production?

With a bright mirror image of quadratic funding: quadratic fees! Imagine

a billboard where anyone can pay $1 to put up an ad for one minute, but

if they want to do this multiple times the prices go up: $2 for the

second minute, $3 for the third minute, etc. Note that you can pay to

extend the lifetime of someone else's ad on the billboard, and

this also costs you only $1 for the first minute, even if other

people already paid to extend the ad's lifetime many times. We can

once again interpret this as being a special case of quadratic voting:

it's basically the same as the "voting on a thermostat" example above,

but where the thermostat in question is the number of seconds an ad

stays up.

This kind of payment model could be applied in cities, on websites,

at conferences, or in many other contexts, if the goal is to optimize

for putting up things that people want to see (or things that people

want other people to see, but even here it's much more democratic than

simply buying space) rather than things that wealthy people and

centralized institutions want people to see.

Complexities and caveats

Perhaps the biggest challenge to consider with this concept of

quadratic payments is the practical implementation issue of identity and

bribery/collusion. Quadratic payments in any form require a model of

identity where individuals cannot easily get as many identities as they

want: if they could, then they could just keep getting new identities

and keep paying $1 to influence some decision as many times as they

want, and the mechanism collapses into linear vote-buying. Note that the

identity system does not need to be airtight (in the sense of

preventing multiple-identity acquisition), and indeed there are good

civil-liberties reasons why identity systems probably should

not try to be airtight. Rather, it just needs to be robust

enough that manipulation is not worth the cost.

Collusion is also tricky. If we can't prevent people from selling

their votes, the mechanisms once again collapse into

one-dollar-one-vote. We don't just need votes to be anonymous and

private (while still making the final result provable and public);

we need votes to be so private that even the person who made the

vote can't prove to anyone else what they voted for. This is

difficult. Secret ballots do this well in the offline world, but secret

ballots are a nineteenth century technology, far too inefficient for the

sheer amount of quadratic voting and funding that we want to see in the

twenty first century.

Fortunately, there are technological

means that can help, combining together zero-knowledge proofs,

encryption and other cryptographic technologies to achieve the precise

desired set of privacy and verifiability properties. There's also proposed

techniques to verify that private keys actually are in an

individual's possession and not in some hardware or cryptographic system

that can restrict how they use those keys. However, these techniques are

all untested and require quite a bit of further work.

Another challenge is that quadratic payments, being a payment-based

mechanism, continues to favor people with more money. Note that because

the cost of votes is quadratic, this effect is dampened: someone with

100 times more money only has 10 times more influence, not 100 times, so

the extent of the problem goes down by 90% (and even more for

ultra-wealthy actors). That said, it may be desirable to mitigate this

inequality of power further. This could be done either by denominating

quadratic payments in a separate token of which everyone gets a fixed

number of units, or giving each person an allocation of funds that can

only be used for quadratic-payments use cases: this is basically Andrew Yang's

"democracy dollars" proposal.

A third challenge is the "rational

ignorance" and "rational

irrationality" problems, which is that decentralized public

decisions have the weakness that any single individual has very little

effect on the outcome, and so little motivation to make sure they are

supporting the decision that is best for the long term; instead,

pressures such as tribal affiliation may dominate. There are many

strands of philosophy that emphasize the ability of large crowds to be

very wrong despite (or because of!) their size, and quadratic payments

in any form do little to address this.

Quadratic payments do better at mitigating this problem than

one-person-one-vote systems, and these problems can be expected to be

less severe for medium-scale public goods than for large decisions that

affect many millions of people, so it may not be a large challenge at

first, but it's certainly an issue worth confronting. One approach is combining

quadratic voting with elements of sortition. Another, potentially

more long-term durable, approach is to combine quadratic voting with

another economic technology that is much more specifically targeted

toward rewarding the "correct contrarianism" that can dispel mass

delusions: prediction

markets. A simple example would be a system where quadratic funding

is done retrospectively, so people vote on which public goods

were valuable some time ago (eg. even 2 years), and projects are funded

up-front by selling shares of the results of these deferred votes; by

buying shares people would be both funding the projects and betting on

which project would be viewed as successful in 2 years' time. There is a

large design space to experiment with here.

Conclusion

As I mentioned at the beginning, quadratic payments do not solve

every problem. They solve the problem of governing resources that affect

large numbers of people, but they do not solve many other kinds of

problems. A particularly important one is information asymmetry and low

quality of information in general. For this reason, I am a fan of

techniques such as prediction markets (see electionbettingodds.com for

one example) to solve information-gathering problems, and many

applications can be made most effective by combining different

mechanisms together.

One particular cause dear to me personally is what I call

"entrepreneurial public goods": public goods that in the present only a

few people believe are important but in the future many more people will

value. In the 19th century, contributing to abolition of slavery may

have been one example; in the 21st century I can't give examples that

will satisfy every reader because it's the nature of these goods that

their importance will only become common knowledge later down the road,

but I would point to life extension

and AI risk research as two

possible examples.

That said, we don't need to solve every problem today. Quadratic

payments are an idea that has only become popular in the last few years;

we still have not seen more than small-scale trials of quadratic voting

and funding, and quadratic attention payments have not been tried at

all! There is still a long way to go. But if we can get these mechanisms

off the ground, there is a lot that these mechanisms have to offer!

Quadratic Payments: A Primer

2019 Dec 07 See all postsSpecial thanks to Karl Floersch and Jinglan Wang for feedback

If you follow applied mechanism design or decentralized governance at all, you may have recently heard one of a few buzzwords: quadratic voting, quadratic funding and quadratic attention purchase. These ideas have been gaining popularity rapidly over the last few years, and small-scale tests have already been deployed: the Taiwanese presidential hackathon used quadratic voting to vote on winning projects, Gitcoin Grants used quadratic funding to fund public goods in the Ethereum ecosystem, and the Colorado Democratic party also experimented with quadratic voting to determine their party platform.

To the proponents of these voting schemes, this is not just another slight improvement to what exists. Rather, it's an initial foray into a fundamentally new class of social technology which, has the potential to overturn how we make many public decisions, large and small. The ultimate effect of these schemes rolled out in their full form could be as deeply transformative as the industrial-era advent of mostly-free markets and constitutional democracy. But now, you may be thinking: "These are large promises. What do these new governance technologies have that justifies such claims?"

Private goods, private markets...

To understand what is going on, let us first consider an existing social technology: money, and property rights - the invisible social technology that generally hides behind money. Money and private property are extremely powerful social technologies, for all the reasons classical economists have been stating for over a hundred years. If Bob is producing apples, and Alice wants to buy apples, we can economically model the interaction between the two, and the results seem to make sense:

Alice keeps buying apples until the marginal value of the next apple to her is less than the cost of producing it, which is pretty much exactly the optimal thing that could happen. This is all formalized in results such as the "fundamental theorems of welfare economics". Now, those of you who have learned some economics may be screaming, but what about imperfect competition? Asymmetric information? Economic inequality? Public goods? Externalities? Many activities in the real world, including those that are key to the progress of human civilization, benefit (or harm) many people in complicated ways. These activities and the consequences that arise from them often cannot be neatly decomposed into sequences of distinct trades between two parties.

But since when do we expect a single package of technologies to solve every problem anyway? "What about oceans?" isn't an argument against cars, it's an argument against car maximalism, the position that we need cars and nothing else. Much like how private property and markets deal with private goods, can we try to use economic means to deduce what kind of social technologies would work well for encouraging production of the public goods that we need?

... Public goods, public markets

Private goods (eg. apples) and public goods (eg. public parks, air quality, scientific research, this article...) are different in some key ways. When we are talking about private goods, production for multiple people (eg. the same farmer makes apples for both Alice and Bob) can be decomposed into (i) the farmer making some apples for Alice, and (ii) the farmer making some other apples for Bob. If Alice wants apples but Bob does not, then the farmer makes Alice's apples, collects payment from Alice, and leaves Bob alone. Even complex collaborations (the "I, Pencil" essay popular in libertarian circles comes to mind) can be decomposed into a series of such interactions. When we are talking about public goods, however, this kind of decomposition is not possible. When I write this blog article, it can be read by both Alice and Bob (and everyone else). I could put it behind a paywall, but if it's popular enough it will inevitably get mirrored on third-party sites, and paywalls are in any case annoying and not very effective. Furthermore, making an article available to ten people is not ten times cheaper than making the article available to a hundred people; rather, the cost is exactly the same. So I either produce the article for everyone, or I do not produce it for anyone at all.

So here comes the challenge: how do we aggregate together people's preferences? Some private and public goods are worth producing, others are not. In the case of private goods, the question is easy, because we can just decompose it into a series of decisions for each individual. Whatever amount each person is willing to pay for, that much gets produced for them; the economics is not especially complex. In the case of public goods, however, you cannot "decompose", and so we need to add up people's preferences in a different way.

First of all, let's see what happens if we just put up a plain old regular market: I offer to write an article as long as at least $1000 of money gets donated to me (fun fact: I literally did this back in 2011). Every dollar donated increases the probability that the goal will be reached and the article will be published; let us call this "marginal probability"

p. At a cost of $k, you can increase the probability that the article will be published byk * p(though eventually the gains will decrease as the probability approaches 100%). Let's say to you personally, the article being published is worth $V. Would you donate? Well, donating a dollar increases the probability it will be published byp, and so gives you an expected $p * Vof value. Ifp * V > 1, you donate, and quite a lot, and ifp * V < 1you don't donate at all.Phrased less mathematically, either you value the article enough (and/or are rich enough) to pay, and if that's the case it's in your interest to keep paying (and influencing) quite a lot, or you don't value the article enough and you contribute nothing. Hence, the only blog articles that get published would be articles where some single person is willing to basically pay for it themselves (in my experiment in 2011, this prediction was experimentally verified: in most rounds, over half of the total contribution came from a single donor).

Note that this reasoning applies for any kind of mechanism that involves "buying influence" over matters of public concern. This includes paying for public goods, shareholder voting in corporations, public advertising, bribing politicians, and much more. The little guy has too little influence (not quite zero, because in the real world things like altruism exist) and the big guy has too much. If you had an intuition that markets work great for buying apples, but money is corrupting in "the public sphere", this is basically a simplified mathematical model that shows why.

We can also consider a different mechanism: one-person-one-vote. Let's say you can either vote that I deserve a reward for writing this article, or you can vote that I don't, and my reward is proportional to the number of votes in my favor. We can interpret this as follows: your first "contribution" costs only a small amount of effort, so you'll support an article if you care about it enough, but after that point there is no more room to contribute further; your second contribution "costs" infinity.

Now, you might notice that neither of the graphs above look quite right. The first graph over-privileges people who care a lot (or are wealthy), the second graph over-privileges people who care only a little, which is also a problem. The single sheep's desire to live is more important than the two wolves' desire to have a tasty dinner.

But what do we actually want? Ultimately, we want a scheme where how much influence you "buy" is proportional to how much you care. In the mathematical lingo above, we want your

kto be proportional to yourV. But here's the problem: yourVdetermines how much you're willing to pay for one unit of influence. If Alice were willing to pay $100 for the article if she had to fund it herself, then she would be willing to pay $1 for an increased 1% chance it will get written, and if Bob were only willing to pay $50 for the article then he would only be willing to pay $0.5 for the same "unit of influence".So how do we match these two up? The answer is clever: your n'th unit of influence costs you $n . That is, for example, you could buy your first vote for $0.01, but then your second would cost $0.02, your third $0.03, and so forth. Suppose you were Alice in the example above; in such a system she would keep buying units of influence until the cost of the next one got to $1, so she would buy 100 units. Bob would similarly buy until the cost got to $0.5, so he would buy 50 units. Alice's 2x higher valuation turned into 2x more units of influence purchased.

Let's draw this as a graph:

Now let's look at all three beside each other:

Notice that only quadratic voting has this nice property that the amount of influence you purchase is proportional to how much you care; the other two mechanisms either over-privilege concentrated interests or over-privilege diffuse interests.

Now, you might ask, where does the quadratic come from? Well, the marginal cost of the n'th vote is $n (or $0.01 * n), but the total cost of n votes is \(\approx \frac{n^2}{2}\). You can view this geometrically as follows:

The total cost is the area of a triangle, and you probably learned in math class that area is base * height / 2. And since here base and height are proportionate, that basically means that total cost is proportional to number of votes squared - hence, "quadratic". But honestly it's easier to think "your n'th unit of influence costs $n".

Finally, you might notice that above I've been vague about what "one unit of influence" actually means. This is deliberate; it can mean different things in different contexts, and the different "flavors" of quadratic payments reflect these different perspectives.

Quadratic Voting

See also the original paper: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract%5fid=2003531

Let us begin by exploring the first "flavor" of quadratic payments: quadratic voting. Imagine that some organization is trying to choose between two choices for some decision that affects all of its members. For example, this could be a company or a nonprofit deciding which part of town to make a new office in, or a government deciding whether or not to implement some policy, or an internet forum deciding whether or not its rules should allow discussion of cryptocurrency prices. Within the context of the organization, the choice made is a public good (or public bad, depending on whom you talk to): everyone "consumes" the results of the same decision, they just have different opinions about how much they like the result.

This seems like a perfect target for quadratic voting. The goal is that option A gets chosen if in total people like A more, and option B gets chosen if in total people like B more. With simple voting ("one person one vote"), the distinction between stronger vs weaker preferences gets ignored, so on issues where one side is of very high value to a few people and the other side is of low value to more people, simple voting is likely to give wrong answers. With a private-goods market mechanism where people can buy as many votes as they want at the same price per vote, the individual with the strongest preference (or the wealthiest) carries everything. Quadratic voting, where you can make n votes in either direction at a cost of n2, is right in the middle between these two extremes, and creates the perfect balance.

Note that in the voting case, we're deciding two options, so different people will favor A over B or B over A; hence, unlike the graphs we saw earlier that start from zero, here voting and preference can both be positive or negative (which option is considered positive and which is negative doesn't matter; the math works out the same way)

As shown above, because the n'th vote has a cost of

n, the number of votes you make is proportional to how much you value one unit of influence over the decision (the value of the decision multiplied by the probability that one vote will tip the result), and hence proportional to how much you care about A being chosen over B or vice versa. Hence, we once again have this nice clean "preference adding" effect.We can extend quadratic voting in multiple ways. First, we can allow voting between more than two options. While traditional voting schemes inevitably fall prey to various kinds of "strategic voting" issues because of Arrow's theorem and Duverger's law, quadratic voting continues to be optimal in contexts with more than two choices.

Second, we can look not just at voting between discrete options, but also at voting on the setting of a thermostat: anyone can push the thermostat up or down by 0.01 degrees n times by paying a cost of n2.

Plot twist: the side wanting it colder only wins when they convince the other side that "C" stands for "caliente".

Quadratic funding

See also the original paper: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract%5fid=3243656

Quadratic voting is optimal when you need to make some fixed number of collective decisions. But one weakness of quadratic voting is that it doesn't come with a built-in mechanism for deciding what goes on the ballot in the first place. Proposing votes is potentially a source of considerable power if not handled with care: a malicious actor in control of it can repeatedly propose some decision that a majority weakly approves of and a minority strongly disapproves of, and keep proposing it until the minority runs out of voting tokens (if you do the math you'll see that the minority would burn through tokens much faster than the majority). Let's consider a flavor of quadratic payments that does not run into this issue, and makes the choice of decisions itself endogenous (ie. part of the mechanism itself). In this case, the mechanism is specialized for one particular use case: individual provision of public goods.

Let us consider an example where someone is looking to produce a public good (eg. a developer writing an open source software program), and we want to figure out whether or not this program is worth funding. But instead of just thinking about one single public good, let's create a mechanism where anyone can raise funds for what they claim to be a public good project. Anyone can make a contribution to any project; a mechanism keeps track of these contributions and then at the end of some period of time the mechanism calculates a payment to each project. The way that this payment is calculated is as follows: for any given project, take the square root of each contributor's contribution, add these values together, and take the square of the result. Or in math speak:

\[(\sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{c_i})^2\]

If that sounds complicated, here it is graphically:

In any case where there is more than one contributor, the computed payment is greater than the raw sum of contributions; the difference comes out of a central subsidy pool (eg. if ten people each donate $1, then the sum-of-square-roots is $10, and the square of that is $100, so the subsidy is $90). Note that if the subsidy pool is not big enough to make the full required payment to every project, we can just divide the subsidies proportionately by whatever constant makes the totals add up to the subsidy pool's budget; you can prove that this solves the tragedy-of-the-commons problem as well as you can with that subsidy budget.

There are two ways to intuitively interpret this formula. First, one can look at it through the "fixing market failure" lens, a surgical fix to the tragedy of the commons problem. In any situation where Alice contributes to a project and Bob also contributes to that same project, Alice is making a contribution to something that is valuable not only to herself, but also to Bob. When deciding how much to contribute, Alice was only taking into account the benefit to herself, not Bob, whom she most likely does not even know. The quadratic funding mechanism adds a subsidy to compensate for this effect, determining how much Alice "would have" contributed if she also took into account the benefit her contribution brings to Bob. Furthermore, we can separately calculate the subsidy for each pair of people (nb. if there are

Npeople there areN * (N-1) / 2pairs), and add up all of these subsidies together, and give Bob the combined subsidy from all pairs. And it turns out that this gives exactly the quadratic funding formula.Second, one can look at the formula through a quadratic voting lens. We interpret the quadratic funding as being a special case of quadratic voting, where the contributors to a project are voting for that project and there is one imaginary participant voting against it: the subsidy pool. Every "project" is a motion to take money from the subsidy pool and give it to that project's creator. Everyone sending \(c_i\) of funds is making \(\sqrt{c_i}\) votes, so there's a total of \(\sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{c_i}\) votes in favor of the motion. To kill the motion, the subsidy pool would need to make more than \(\sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{c_i}\) votes against it, which would cost it more than \((\sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{c_i})^2\). Hence, \((\sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{c_i})^2\) is the maximum transfer from the subsidy pool to the project that the subsidy pool would not vote to stop.

Quadratic funding is starting to be explored as a mechanism for funding public goods already; Gitcoin grants for funding public goods in the Ethereum ecosystem is currently the biggest example, and the most recent round led to results that, in my own view, did a quite good job of making a fair allocation to support projects that the community deems valuable.

Numbers in white are raw contribution totals; numbers in green are the extra subsidies.

Quadratic attention payments

See also the original post: https://kortina.nyc/essays/speech-is-free-distribution-is-not-a-tax-on-the-purchase-of-human-attention-and-political-power/

One of the defining features of modern capitalism that people love to hate is ads. Our cities have ads:

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/argonavigo/36657795264

Our subway turnstiles have ads:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NYC,_subway_ad_on_Prince_St.jpg

Our politics are dominated by ads:

Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e3/Billboard_Challenging_the_validity_of_Barack_Obama%27s_Birth_Certificate.JPG

And even the rivers and the skies have ads. Now, there are some places that seem to not have this problem:

But really they just have a different kind of ads:

Now, recently there are attempts to move beyond this in some cities. And on Twitter. But let's look at the problem systematically and try to see what's going wrong. The answer is actually surprisingly simple: public advertising is the evil twin of public goods production. In the case of public goods production, there is one actor that is taking on an expenditure to produce some product, and this product benefits a large number of people. Because these people cannot effectively coordinate to pay for the public goods by themselves, we get much less public goods than we need, and the ones we do get are those favored by wealthy actors or centralized authorities. Here, there is one actor that reaps a large benefit from forcing other people to look at some image, and this action harms a large number of people. Because these people cannot effectively coordinate to buy out the slots for the ads, we get ads we don't want to see, that are favored by... wealthy actors or centralized authorities.

So how do we solve this dark mirror image of public goods production? With a bright mirror image of quadratic funding: quadratic fees! Imagine a billboard where anyone can pay $1 to put up an ad for one minute, but if they want to do this multiple times the prices go up: $2 for the second minute, $3 for the third minute, etc. Note that you can pay to extend the lifetime of someone else's ad on the billboard, and this also costs you only $1 for the first minute, even if other people already paid to extend the ad's lifetime many times. We can once again interpret this as being a special case of quadratic voting: it's basically the same as the "voting on a thermostat" example above, but where the thermostat in question is the number of seconds an ad stays up.

This kind of payment model could be applied in cities, on websites, at conferences, or in many other contexts, if the goal is to optimize for putting up things that people want to see (or things that people want other people to see, but even here it's much more democratic than simply buying space) rather than things that wealthy people and centralized institutions want people to see.

Complexities and caveats

Perhaps the biggest challenge to consider with this concept of quadratic payments is the practical implementation issue of identity and bribery/collusion. Quadratic payments in any form require a model of identity where individuals cannot easily get as many identities as they want: if they could, then they could just keep getting new identities and keep paying $1 to influence some decision as many times as they want, and the mechanism collapses into linear vote-buying. Note that the identity system does not need to be airtight (in the sense of preventing multiple-identity acquisition), and indeed there are good civil-liberties reasons why identity systems probably should not try to be airtight. Rather, it just needs to be robust enough that manipulation is not worth the cost.

Collusion is also tricky. If we can't prevent people from selling their votes, the mechanisms once again collapse into one-dollar-one-vote. We don't just need votes to be anonymous and private (while still making the final result provable and public); we need votes to be so private that even the person who made the vote can't prove to anyone else what they voted for. This is difficult. Secret ballots do this well in the offline world, but secret ballots are a nineteenth century technology, far too inefficient for the sheer amount of quadratic voting and funding that we want to see in the twenty first century.

Fortunately, there are technological means that can help, combining together zero-knowledge proofs, encryption and other cryptographic technologies to achieve the precise desired set of privacy and verifiability properties. There's also proposed techniques to verify that private keys actually are in an individual's possession and not in some hardware or cryptographic system that can restrict how they use those keys. However, these techniques are all untested and require quite a bit of further work.

Another challenge is that quadratic payments, being a payment-based mechanism, continues to favor people with more money. Note that because the cost of votes is quadratic, this effect is dampened: someone with 100 times more money only has 10 times more influence, not 100 times, so the extent of the problem goes down by 90% (and even more for ultra-wealthy actors). That said, it may be desirable to mitigate this inequality of power further. This could be done either by denominating quadratic payments in a separate token of which everyone gets a fixed number of units, or giving each person an allocation of funds that can only be used for quadratic-payments use cases: this is basically Andrew Yang's "democracy dollars" proposal.

A third challenge is the "rational ignorance" and "rational irrationality" problems, which is that decentralized public decisions have the weakness that any single individual has very little effect on the outcome, and so little motivation to make sure they are supporting the decision that is best for the long term; instead, pressures such as tribal affiliation may dominate. There are many strands of philosophy that emphasize the ability of large crowds to be very wrong despite (or because of!) their size, and quadratic payments in any form do little to address this.

Quadratic payments do better at mitigating this problem than one-person-one-vote systems, and these problems can be expected to be less severe for medium-scale public goods than for large decisions that affect many millions of people, so it may not be a large challenge at first, but it's certainly an issue worth confronting. One approach is combining quadratic voting with elements of sortition. Another, potentially more long-term durable, approach is to combine quadratic voting with another economic technology that is much more specifically targeted toward rewarding the "correct contrarianism" that can dispel mass delusions: prediction markets. A simple example would be a system where quadratic funding is done retrospectively, so people vote on which public goods were valuable some time ago (eg. even 2 years), and projects are funded up-front by selling shares of the results of these deferred votes; by buying shares people would be both funding the projects and betting on which project would be viewed as successful in 2 years' time. There is a large design space to experiment with here.

Conclusion

As I mentioned at the beginning, quadratic payments do not solve every problem. They solve the problem of governing resources that affect large numbers of people, but they do not solve many other kinds of problems. A particularly important one is information asymmetry and low quality of information in general. For this reason, I am a fan of techniques such as prediction markets (see electionbettingodds.com for one example) to solve information-gathering problems, and many applications can be made most effective by combining different mechanisms together.

One particular cause dear to me personally is what I call "entrepreneurial public goods": public goods that in the present only a few people believe are important but in the future many more people will value. In the 19th century, contributing to abolition of slavery may have been one example; in the 21st century I can't give examples that will satisfy every reader because it's the nature of these goods that their importance will only become common knowledge later down the road, but I would point to life extension and AI risk research as two possible examples.

That said, we don't need to solve every problem today. Quadratic payments are an idea that has only become popular in the last few years; we still have not seen more than small-scale trials of quadratic voting and funding, and quadratic attention payments have not been tried at all! There is still a long way to go. But if we can get these mechanisms off the ground, there is a lot that these mechanisms have to offer!