Why sharding is great: demystifying the technical properties

2021 Apr 07

See all posts

Why sharding is great: demystifying the technical properties

Special thanks to Dankrad Feist and Aditya Asgaonkar for

review

Sharding is the future of Ethereum scalability, and it will be key to

helping the ecosystem support many thousands of transactions per second

and allowing large portions of the world to regularly use the platform

at an affordable cost. However, it is also one of the more misunderstood

concepts in the Ethereum ecosystem and in blockchain ecosystems more

broadly. It refers to a very specific set of ideas with very specific

properties, but it often gets conflated with techniques that have very

different and often much weaker security properties. The purpose of this

post will be to explain exactly what specific properties sharding

provides, how it differs from other technologies that are not

sharding, and what sacrifices a sharded system has to make to achieve

these properties.

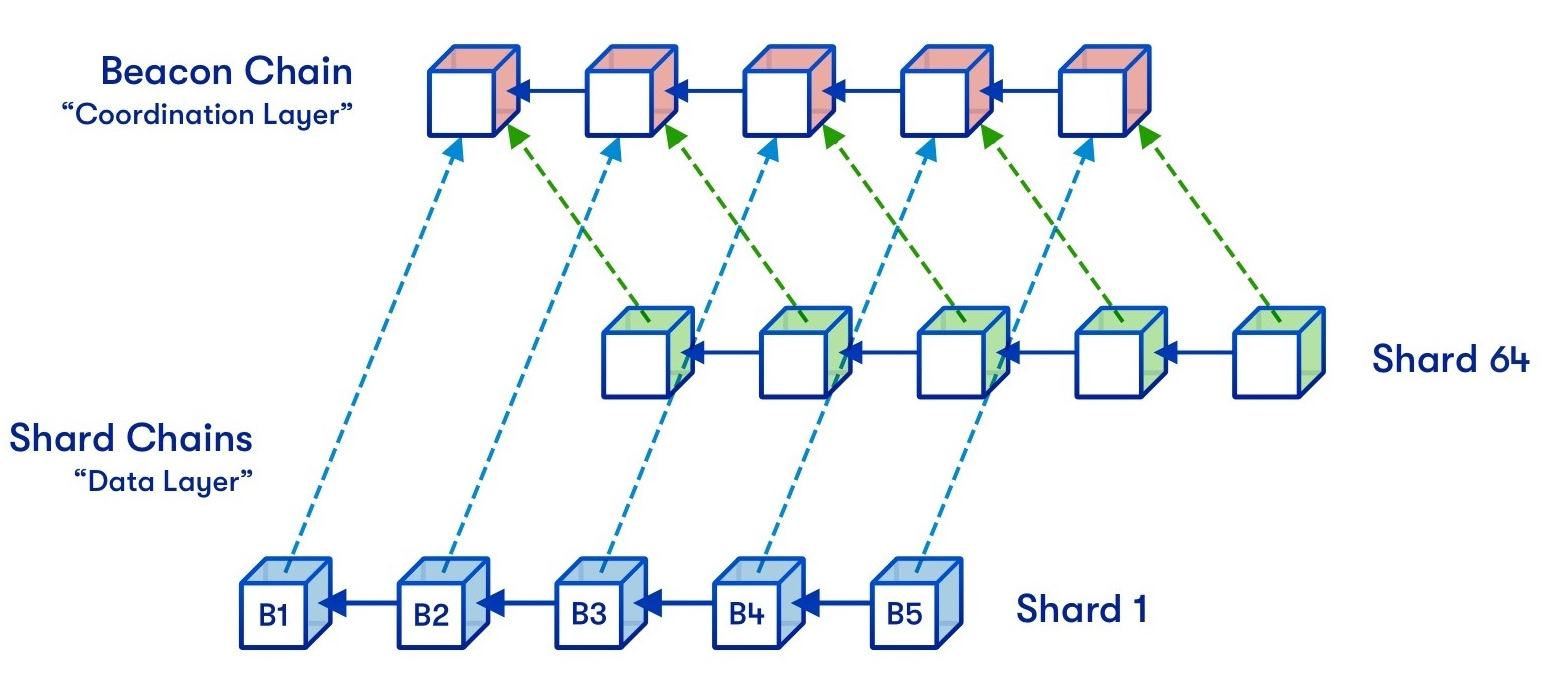

One of the many depictions of a sharded version of Ethereum.

Original diagram by Hsiao-wei Wang, design by

Quantstamp.

One of the many depictions of a sharded version of Ethereum.

Original diagram by Hsiao-wei Wang, design by

Quantstamp.

The Scalability Trilemma

The best way to describe sharding starts from the problem statement

that shaped and inspired the solution: the Scalability

Trilemma.

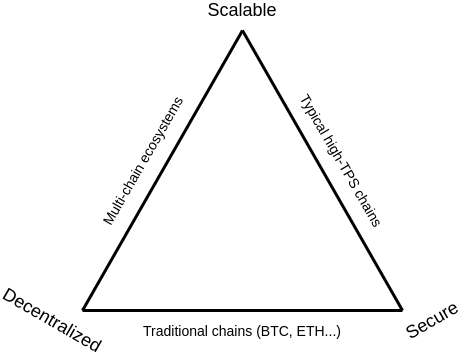

The scalability trilemma says that there are three properties that a

blockchain try to have, and that, if you stick to "simple"

techniques, you can only get two of those three. The three

properties are:

- Scalability: the chain can process more

transactions than a single regular node (think: a consumer laptop) can

verify.

- Decentralization: the chain can run without any

trust dependencies on a small group of large centralized actors. This is

typically interpreted to mean that there should not be any trust (or

even honest-majority assumption) of a set of nodes that you cannot join

with just a consumer laptop.

- Security: the chain can resist a large percentage

of participating nodes trying to attack it (ideally 50%; anything above

25% is fine, 5% is definitely not fine).

Now we can look at the three classes of "easy solutions" that only

get two of the three:

- Traditional blockchains - including Bitcoin,

pre-PoS/sharding Ethereum, Litecoin, and other similar chains. These

rely on every participant running a full node that verifies every

transaction, and so they have decentralization and security, but not

scalability.

- High-TPS chains - including the DPoS family but

also many others. These rely on a small number of nodes (often 10-100)

maintaining consensus among themselves, with users having to trust a

majority of these nodes. This is scalable and secure (using the

definitions above), but it is not decentralized.

- Multi-chain ecosystems - this refers to the general

concept of "scaling out" by having different applications live on

different chains and using cross-chain-communication protocols to talk

between them. This is decentralized and scalable, but it is not secure,

because an attacker need only get a consensus node majority in one of

the many chains (so often <1% of the whole ecosystem) to break that

chain and possibly cause ripple effects that cause great damage to

applications in other chains.

Sharding is a technique that gets you all three. A

sharded blockchain is:

- Scalable: it can process far more transactions than

a single node

- Decentralized: it can survive entirely on consumer

laptops, with no dependency on "supernodes" whatsoever

- Secure: an attacker can't target a small part of

the system with a small amount of resources; they can only try to

dominate and attack the whole thing

The rest of the post will be describing how sharded blockchains

manage to do this.

Sharding through Random

Sampling

The easiest version of sharding to understand is sharding through

random sampling. Sharding through random sampling has weaker trust

properties than the forms of sharding that we are building towards in

the Ethereum ecosystem, but it uses simpler technology.

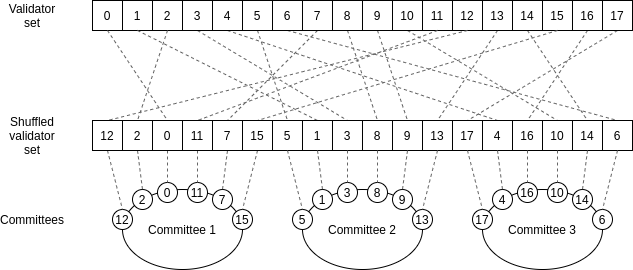

The core idea is as follows. Suppose that you have a proof of stake

chain with a large number (eg. 10000) validators, and you have a large

number (eg. 100) blocks that need to be verified. No single computer is

powerful enough to validate all of these blocks before the next

set of blocks comes in.

Hence, what we do is we randomly split up the work of doing

the verification. We randomly shuffle the validator list, and

we assign the first 100 validators in the shuffled list to verify the

first block, the second 100 validators in the shuffled list to verify

the second block, etc. A randomly selected group of validators that gets

assigned to verify a block (or perform some other task) is called a

committee.

When a validator verifies a block, they publish a signature attesting

to the fact that they did so. Everyone else, instead of verifying 100

entire blocks, now only verifies 10000 signatures - a much smaller

amount of work, especially with BLS

signature aggregation. Instead of every block being broadcasted

through the same P2P network, each block is broadcasted on a different

sub-network, and nodes need only join the subnets corresponding to the

blocks that they are responsible for (or are interested in for other

reasons).

Consider what happens if each node's computing power increases by 2x.

Because each node can now safely validate 2x more signatures, you could

cut the minimum staking deposit size to support 2x more validators, and

so hence you can make 200 committees instead of 100. Hence, you can

verify 200 blocks per slot instead of 100. Furthermore, each

individual block could be 2x bigger. Hence, you have 2x more blocks

of 2x the size, or 4x more chain capacity altogether.

We can introduce some math lingo to talk about what's going on. Using

Big O

notation, we use "O(C)" to refer to the

computational capacity of a single node. A traditional blockchain can

process blocks of size O(C). A sharded chain as

described above can process O(C) blocks in parallel

(remember, the cost to each node to verify each block indirectly is

O(1) because each node only needs to verify a fixed

number of signatures), and each block has O(C)

capacity, and so the sharded chain's total capacity is

O(C2). This is why we call this type of

sharding quadratic sharding, and this effect is a key

reason why we think that in the long run, sharding is the best way to

scale a blockchain.

Frequently

asked question: how is splitting into 100 committees different from

splitting into 100 separate chains?

There are two key differences:

- The random sampling prevents the attacker from concentrating

their power on one shard. In a 100-chain multichain ecosystem,

the attacker only needs ~0.5% of the total stake to wreak havoc: they

can focus on 51% attacking a single chain. In a sharded blockchain, the

attacker must have close to ~30-40% of the entire stake to do

the same (in other words, the chain has shared

security). Certainly, they can wait until they get lucky and

get 51% in a single shard by random chance despite having less than 50%

of the total stake, but this gets exponentially harder for attackers

that have much less than 51%. If an attacker has less than ~30%, it's

virtually impossible.

- Tight coupling: if even one shard gets a bad block, the

entire chain reorgs to avoid it. There is a social contract

(and in later sections of this document we describe some ways to enforce

this technologically) that a chain with even one bad block in even one

shard is not acceptable and should get thrown out as soon as it is

discovered. This ensures that from the point of view of an application

within the chain, there is perfect security: contract A can

rely on contract B, because if contract B misbehaves due to an attack on

the chain, that entire history reverts, including the transactions in

contract A that misbehaved as a result of the malfunction in contract

B.

Both of these differences ensure that sharding creates an environment

for applications that preserves the key safety properties of a

single-chain environment, in a way that multichain ecosystems

fundamentally do not.

Improving

sharding with better security models

One common refrain in Bitcoin circles, and one that I completely

agree with, is that blockchains like Bitcoin (or Ethereum) do

NOT completely rely on an honest majority assumption. If there

is a 51% attack on such a blockchain, then the attacker can do

some nasty things, like reverting or censoring transactions,

but they cannot insert invalid transactions. And even if they do revert

or censor transactions, users running regular nodes could easily detect

that behavior, so if the community wishes to coordinate to resolve the

attack with a fork that takes away the attacker's power they could do so

quickly.

The lack of this extra security is a key weakness of the more

centralized high-TPS chains. Such chains do not, and cannot,

have a culture of regular users running nodes, and so the major nodes

and ecosystem players can much more easily get together and impose a

protocol change that the community heavily dislikes. Even worse, the

users' nodes would by default accept it. After some time, users would

notice, but by then the forced protocol change would be a fait accompli:

the coordination burden

would be on users to reject the change, and they would have to make

the painful decision to revert a day's worth or more of activity that

everyone had thought was already finalized.

Ideally, we want to have a form of sharding that avoids 51%

trust assumptions for validity, and preserves the powerful bulwark of

security that traditional blockchains get from full verification. And

this is exactly what much of our research over the last few years has

been about.

Scalable verification of

computation

We can break up the 51%-attack-proof scalable validation problem into

two cases:

- Validating computation: checking that some

computation was done correctly, assuming you have possession of all the

inputs to the computation

- Validating data availability: checking that the

inputs to the computation themselves are stored in some form where you

can download them if you really need to; this checking should be

performed without actually downloading the entire inputs

themselves (because the data could be too large to download for every

block)

Validating a block in a blockchain involves both computation and data

availability checking: you need to be convinced that the transactions in

the block are valid and that the new state root hash claimed in the

block is the correct result of executing those transactions, but you

also need to be convinced that enough data from the block was actually

published so that users who download that data can compute the state and

continue processing the blockchain. This second part is a very subtle

but important concept called the data

availability problem; more on this later.

Scalably validating computation is relatively easy; there are two

families of techniques: fraud proofs and

ZK-SNARKs.

Fraud proofs are one way to verify computation

scalably.

The two technologies can be described simply as follows:

- Fraud proofs are a system where to accept the

result of a computation, you require someone with a staked

deposit to sign a message of the form "I certify that

if you make computation

C with input X, you

get output Y". You trust these messages by default, but you

leave open the opportunity for someone else with a staked deposit to

make a challenge (a signed message saying "I disagree,

the output is Z"). Only when there is a challenge, all nodes run the

computation. Whichever of the two parties was wrong loses their deposit,

and all computations that depend on the result of that computation are

recomputed.

- ZK-SNARKs are a form of cryptographic

proof that directly proves the claim "performing computation

C on input X gives output Y". The

proof is cryptographically "sound": if C(x) does

not equal Y, it's computationally infeasible to

make a valid proof. The proof is also quick to verify, even if running

C itself takes a huge amount of time. See this post for more

mathematical details on ZK-SNARKs.

Computation based on fraud proofs is scalable because "in the normal

case" you replace running a complex computation with verifying a single

signature. There is the exceptional case, where you do have to verify

the computation on-chain because there is a challenge, but the

exceptional case is very rare because triggering it is very expensive

(either the original claimer or the challenger loses a large deposit).

ZK-SNARKs are conceptually simpler - they just replace a computation

with a much cheaper proof verification - but the math behind how they

work is considerably more complex.

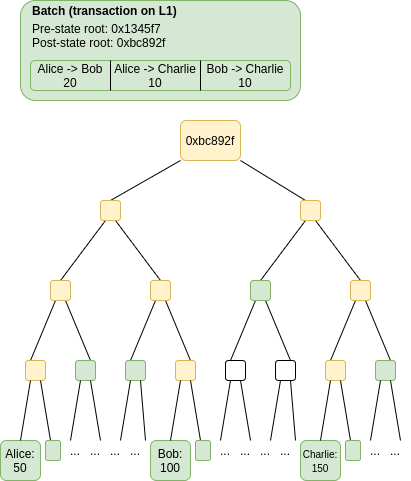

There is a class of semi-scalable system which only scalably

verifies computation, while still requiring every node to verify all the

data. This can be made quite effective by using a set of compression

tricks to replace most data with computation. This is the realm of rollups.

Scalable

verification of data availability is harder

A fraud proof cannot be used to verify availability of data. Fraud

proofs for computation rely on the fact that the inputs to the

computation are published on-chain the moment the original claim is

submitted, and so if someone challenges, the challenge execution is

happening in the exact same "environment" that the original execution

was happening. In the case of checking data availability, you cannot do

this, because the problem is precisely the fact that there is too much

data to check to publish it on chain. Hence, a fraud proof scheme for

data availability runs into a key problem: someone could claim "data X

is available" without publishing it, wait to get challenged, and only

then publish data X and make the challenger appear to the rest

of the network to be incorrect.

This is expanded on in the

fisherman's dilemma:

The core idea is that the two "worlds", one where V1 is an evil

publisher and V2 is an honest challenger and the other where V1 is an

honest publisher and V2 is an evil challenger, are indistinguishable to

anyone who was not trying to download that particular piece of data at

the time. And of course, in a scalable decentralized blockchain, each

individual node can only hope to download a small portion of the data,

so only a small portion of nodes would see anything about what went on

except for the mere fact that there was a disagreement.

The fact that it is impossible to distinguish who was right and who

was wrong makes it impossible to have a working fraud proof scheme for

data availability.

Frequently

asked question: so what if some data is unavailable? With a ZK-SNARK you

can be sure everything is valid, and isn't that enough?

Unfortunately, mere validity is not sufficient to ensure a correctly

running blockchain. This is because if the blockchain is valid

but all the data is not available, then users have no way of

updating the data that they need to generate proofs that any

future block is valid. An attacker that generates a

valid-but-unavailable block but then disappears can effectively stall

the chain. Someone could also withhold a specific user's account data

until the user pays a ransom, so the problem is not purely a liveness

issue.

There are some strong information-theoretic arguments that this

problem is fundamental, and there is no clever trick (eg. involving cryptographic

accumulators) that can get around it. See this paper for

details.

So,

how do you check that 1 MB of data is available without actually trying

to download it? That sounds impossible!

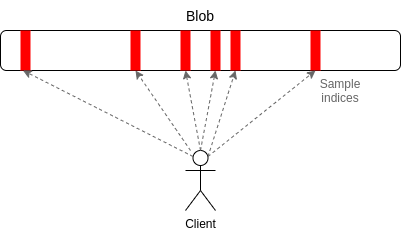

The key is a technology called data

availability sampling. Data availability sampling works as

follows:

- Use a tool called erasure coding to expand a piece

of data with N chunks into a piece of data with 2N chunks such that

any N of those chunks can recover the entire data.

- To check for availability, instead of trying to download the

entire data, users simply randomly select a constant

number of positions in the block (eg. 30 positions), and accept

the block only when they have successfully found the chunks in the block

at all of their selected positions.

Erasure codes transform a "check for 100% availability" (every single

piece of data is available) problem into a "check for 50% availability"

(at least half of the pieces are available) problem. Random sampling

solves the 50% availability problem. If less than 50% of the data is

available, then at least one of the checks will almost certainly fail,

and if at least 50% of the data is available then, while some nodes may

fail to recognize a block as available, it takes only one honest node to

run the erasure code reconstruction procedure to bring back the

remaining 50% of the block. And so, instead of needing to download 1 MB

to check the availability of a 1 MB block, you need only download a few

kilobytes. This makes it feasible to run data availability checking on

every block. See this

post for how this checking can be efficiently implemented with

peer-to-peer subnets.

A ZK-SNARK can be used to verify that the erasure coding on a piece

of data was done correctly, and then Merkle branches can be

used to verify individual chunks. Alternatively, you can use

polynomial commitments (eg. Kate

(aka KZG) commitments), which essentially do erasure coding

and proving individual elements and correctness

verification all in one simple component - and that's what Ethereum

sharding is using.

Recap:

how are we ensuring everything is correct again?

Suppose that you have 100 blocks and you want to efficiently verify

correctness for all of them without relying on committees. We need to do

the following:

- Each client performs data availability sampling on

each block, verifying that the data in each block is available, while

downloading only a few kilobytes per block even if the block as a whole

is a megabyte or larger in size. A client only accepts a block when all

data of their availability challenges have been correctly responded

to.

- Now that we have verified data availability, it becomes easier to

verify correctness. There are two techniques:

- We can use fraud proofs: a few participants with

staked deposits can sign off on each block's correctness. Other nodes,

called challengers (or fishermen)

randomly check and attempt to fully process blocks. Because we already

checked data availability, it will always be possible to download the

data and fully process any particular block. If they find an invalid

block, they post a challenge that everyone verifies. If

the block turns out to be bad, then that block and all future blocks

that depend on that need to be re-computed.

- We can use ZK-SNARKs. Each block would come with a

ZK-SNARK proving correctness.

- In either of the above cases, each client only needs to do a small

amount of verification work per block, no matter how big the block is.

In the case of fraud proofs, occasionally blocks will need to be fully

verified on-chain, but this should be extremely rare because triggering

even one challenge is very expensive.

And that's all there is to it! In the case of Ethereum sharding, the

near-term plan is to make sharded blocks data-only;

that is, the shards are purely a "data availability engine",

and it's the job of layer-2 rollups to

use that secure data space, plus either fraud proofs or ZK-SNARKs, to

implement high-throughput secure transaction processing capabilities.

However, it's completely possible to create such a built-in system to

add "native" high-throughput execution.

What

are the key properties of sharded systems and what are the

tradeoffs?

The key goal of sharding is to come as close as possible to

replicating the most important security properties of traditional

(non-sharded) blockchains but without the need for each node to

personally verify each transaction.

Sharding comes quite close. In a traditional blockchain:

- Invalid blocks cannot get through because

validating nodes notice that they are invalid and ignore them.

- Unavailable blocks cannot get through because

validating nodes fail to download them and ignore them.

In a sharded blockchain with advanced security features:

- Invalid blocks cannot get through because either:

- A fraud proof quickly catches them and informs the entire network of

the block's incorrectness, and heavily penalizes the creator, or

- A ZK-SNARK proves correctness, and you cannot make a valid ZK-SNARK

for an invalid block.

- Unavailable blocks cannot get through because:

- If less than 50% of a block's data is available, at least one data

availability sample check will almost certainly fail for each client,

causing the client to reject the block,

- If at least 50% of a block's data is available, then actually the

entire block is available, because it takes only a single honest node to

reconstruct the rest of the block.

Traditional high-TPS chains without sharding do not have a way of

providing these guarantees. Multichain ecosystems do not have a way of

avoiding the problem of an attacker selecting one chain for attack and

easily taking it over (the chains could share security, but if

this was done poorly it would turn into a de-facto traditional high-TPS

chain with all its disadvantages, and if it was done well, it would just

be a more complicated implementation of the above sharding

techniques).

Sidechains are highly implementation-dependent, but

they are typically vulnerable to either the weaknesses of traditional

high-TPS chains (this is if they share miners/validators), or the

weaknesses of multichain ecosystems (this is if they do not share

miners/validators). Sharded chains avoid these issues.

However, there are some chinks in the sharded system's

armor. Notably:

- Sharded chains that rely only on committees are

vulnerable to adaptive adversaries, and have weaker

accountability. That is, if the adversary has the ability to

hack into (or just shut down) any set of nodes of their choosing in real

time, then they only need to attack a small number of nodes to break a

single committee. Furthermore, if an adversary (whether an adaptive

adversary or just an attacker with 50% of the total stake) does break a

single committee, only a few of their nodes (the ones in that committee)

can be publicly confirmed to be participating in that attack, and so

only a small amount of stake can be penalized. This is another key

reason why data availability sampling together with either fraud proofs

or ZK-SNARKs are an important complement to random sampling

techniques.

- Data availability sampling is only secure if there is a

sufficient number of online clients that they collectively make

enough data availability sampling requests that the responses almost

always overlap to comprise at least 50% of the block. In practice, this

means that there must be a few hundred clients online

(and this number increases the higher the ratio of the capacity of the

system to the capacity of a single node). This is a few-of-N trust model -

generally quite trustworthy, but certainly not as robust as the 0-of-N

trust that nodes in non-sharded chains have for availability.

- If the sharded chain relies on fraud proofs, then it relies

on timing assumptions; if the network is too slow, nodes could

accept a block as finalized before the fraud proof comes in showing that

it is wrong. Fortunately, if you follow a strict rule of reverting all

invalid blocks once the invalidity is discovered, this threshold is a

user-set parameter: each individual user chooses how long they wait

until finality and if they didn't want long enough then suffer, but more

careful users are safe. Even still, this is a weakening of the user

experience. Using ZK-SNARKs to verify validity solves

this.

- There is a much larger amount of raw data that needs to be

passed around, increasing the risk of failures under extreme

networking conditions. Small amounts of data are easier to send (and

easier to safely

hide, if a powerful government attempts to censor the chain) than

larger amounts of data. Block explorers need to store more data if they

want to hold the entire chain.

- Sharded blockchains depend on sharded peer-to-peer networks, and

each individual p2p "subnet" is easier to attack because it has

fewer nodes. The subnet

model used for data availability sampling mitigates this because

there is some redundancy between subnets, but even still there is a

risk.

These are valid concerns, though in our view they are far outweighed

by the reduction in user-level centralization enabled by

allowing more applications to run on-chain instead of through

centralized layer-2 services. That said, these concerns, especially the

last two, are in practice the real constraint on increasing a sharded

chain's throughput beyond a certain point. There is a limit to the

quadraticness of quadratic sharding.

Incidentally, the growing safety risks of sharded blockchains if

their throughput becomes too high are also the key reason why the effort

to extend to super-quadratic sharding has been largely

abandoned; it looks like keeping quadratic sharding just

quadratic really is the happy medium.

Why not

centralized production and sharded verification?

One alternative to sharding that gets often proposed is to have a

chain that is structured like a centralized high-TPS chain, except it

uses data availability sampling and sharding on top to allow

verification of validity and availability.

This improves on centralized high-TPS chains as they exist today, but

it's still considerably weaker than a sharded system. This is for a few

reasons:

- It's much harder to detect censorship by block producers in

a high-TPS chain. Censorship detection requires either (i)

being able to see every transaction and verify that there are

no transactions that clearly deserve to get in that inexplicably fail to

get in, or (ii) having a 1-of-N trust model in block producers

and verifying that no blocks fail to get in. In a centralized high-TPS

chain, (i) is impossible, and (ii) is harder because the small node

count makes even a 1-of-N trust model more likely to break, and if the

chain has a block time that is too fast for DAS (as most centralized

high-TPS chains do), it's very hard to prove that a node's blocks are

not being rejected simply because they are all being published too

slowly.

- If a majority of block producers and ecosystem members tries to

force through an unpopular protocol change, users' clients will

certainly detect it, but it's much harder for the

community to rebel and fork away because they would need to

spin up a new set of very expensive high-throughput nodes to maintain a

chain that keeps the old rules.

- Centralized infrastructure is more vulnerable to censorship

imposed by external actors. The high throughput of the block

producing nodes makes them very detectable and easier to shut down. It's

also politically and logistically easier to censor dedicated

high-performance computation than it is to go after individual users'

laptops.

- There's a stronger pressure for high-performance computation

to move to centralized cloud services, increasing the risk that

the entire chain will be run within 1-3 companies' cloud services, and

hence risk of the chain going down because of many block producers

failing simultaneously. A sharded chain with a culture of running

validators on one's own hardware is again much less vulnerable to

this.

Properly sharded systems are better as a base layer. Given a sharded

base layer, you can always create a centralized-production system (eg.

because you want a high-throughput domain with synchronous

composability for defi) layered on top by building it as a rollup.

But if you have a base layer with a dependency on centralized block

production, you cannot build a more-decentralized layer 2 on top.

Why sharding is great: demystifying the technical properties

2021 Apr 07 See all postsSpecial thanks to Dankrad Feist and Aditya Asgaonkar for review

Sharding is the future of Ethereum scalability, and it will be key to helping the ecosystem support many thousands of transactions per second and allowing large portions of the world to regularly use the platform at an affordable cost. However, it is also one of the more misunderstood concepts in the Ethereum ecosystem and in blockchain ecosystems more broadly. It refers to a very specific set of ideas with very specific properties, but it often gets conflated with techniques that have very different and often much weaker security properties. The purpose of this post will be to explain exactly what specific properties sharding provides, how it differs from other technologies that are not sharding, and what sacrifices a sharded system has to make to achieve these properties.

The Scalability Trilemma

The best way to describe sharding starts from the problem statement that shaped and inspired the solution: the Scalability Trilemma.

The scalability trilemma says that there are three properties that a blockchain try to have, and that, if you stick to "simple" techniques, you can only get two of those three. The three properties are:

Now we can look at the three classes of "easy solutions" that only get two of the three:

Sharding is a technique that gets you all three. A sharded blockchain is:

The rest of the post will be describing how sharded blockchains manage to do this.

Sharding through Random Sampling

The easiest version of sharding to understand is sharding through random sampling. Sharding through random sampling has weaker trust properties than the forms of sharding that we are building towards in the Ethereum ecosystem, but it uses simpler technology.

The core idea is as follows. Suppose that you have a proof of stake chain with a large number (eg. 10000) validators, and you have a large number (eg. 100) blocks that need to be verified. No single computer is powerful enough to validate all of these blocks before the next set of blocks comes in.

Hence, what we do is we randomly split up the work of doing the verification. We randomly shuffle the validator list, and we assign the first 100 validators in the shuffled list to verify the first block, the second 100 validators in the shuffled list to verify the second block, etc. A randomly selected group of validators that gets assigned to verify a block (or perform some other task) is called a committee.

When a validator verifies a block, they publish a signature attesting to the fact that they did so. Everyone else, instead of verifying 100 entire blocks, now only verifies 10000 signatures - a much smaller amount of work, especially with BLS signature aggregation. Instead of every block being broadcasted through the same P2P network, each block is broadcasted on a different sub-network, and nodes need only join the subnets corresponding to the blocks that they are responsible for (or are interested in for other reasons).

Consider what happens if each node's computing power increases by 2x. Because each node can now safely validate 2x more signatures, you could cut the minimum staking deposit size to support 2x more validators, and so hence you can make 200 committees instead of 100. Hence, you can verify 200 blocks per slot instead of 100. Furthermore, each individual block could be 2x bigger. Hence, you have 2x more blocks of 2x the size, or 4x more chain capacity altogether.

We can introduce some math lingo to talk about what's going on. Using Big O notation, we use "O(C)" to refer to the computational capacity of a single node. A traditional blockchain can process blocks of size O(C). A sharded chain as described above can process O(C) blocks in parallel (remember, the cost to each node to verify each block indirectly is O(1) because each node only needs to verify a fixed number of signatures), and each block has O(C) capacity, and so the sharded chain's total capacity is O(C2). This is why we call this type of sharding quadratic sharding, and this effect is a key reason why we think that in the long run, sharding is the best way to scale a blockchain.

Frequently asked question: how is splitting into 100 committees different from splitting into 100 separate chains?

There are two key differences:

Both of these differences ensure that sharding creates an environment for applications that preserves the key safety properties of a single-chain environment, in a way that multichain ecosystems fundamentally do not.

Improving sharding with better security models

One common refrain in Bitcoin circles, and one that I completely agree with, is that blockchains like Bitcoin (or Ethereum) do NOT completely rely on an honest majority assumption. If there is a 51% attack on such a blockchain, then the attacker can do some nasty things, like reverting or censoring transactions, but they cannot insert invalid transactions. And even if they do revert or censor transactions, users running regular nodes could easily detect that behavior, so if the community wishes to coordinate to resolve the attack with a fork that takes away the attacker's power they could do so quickly.

The lack of this extra security is a key weakness of the more centralized high-TPS chains. Such chains do not, and cannot, have a culture of regular users running nodes, and so the major nodes and ecosystem players can much more easily get together and impose a protocol change that the community heavily dislikes. Even worse, the users' nodes would by default accept it. After some time, users would notice, but by then the forced protocol change would be a fait accompli: the coordination burden would be on users to reject the change, and they would have to make the painful decision to revert a day's worth or more of activity that everyone had thought was already finalized.

Ideally, we want to have a form of sharding that avoids 51% trust assumptions for validity, and preserves the powerful bulwark of security that traditional blockchains get from full verification. And this is exactly what much of our research over the last few years has been about.

Scalable verification of computation

We can break up the 51%-attack-proof scalable validation problem into two cases:

Validating a block in a blockchain involves both computation and data availability checking: you need to be convinced that the transactions in the block are valid and that the new state root hash claimed in the block is the correct result of executing those transactions, but you also need to be convinced that enough data from the block was actually published so that users who download that data can compute the state and continue processing the blockchain. This second part is a very subtle but important concept called the data availability problem; more on this later.

Scalably validating computation is relatively easy; there are two families of techniques: fraud proofs and ZK-SNARKs.

Fraud proofs are one way to verify computation scalably.

The two technologies can be described simply as follows:

Cwith inputX, you get outputY". You trust these messages by default, but you leave open the opportunity for someone else with a staked deposit to make a challenge (a signed message saying "I disagree, the output is Z"). Only when there is a challenge, all nodes run the computation. Whichever of the two parties was wrong loses their deposit, and all computations that depend on the result of that computation are recomputed.Con inputXgives outputY". The proof is cryptographically "sound": ifC(x)does not equalY, it's computationally infeasible to make a valid proof. The proof is also quick to verify, even if runningCitself takes a huge amount of time. See this post for more mathematical details on ZK-SNARKs.Computation based on fraud proofs is scalable because "in the normal case" you replace running a complex computation with verifying a single signature. There is the exceptional case, where you do have to verify the computation on-chain because there is a challenge, but the exceptional case is very rare because triggering it is very expensive (either the original claimer or the challenger loses a large deposit). ZK-SNARKs are conceptually simpler - they just replace a computation with a much cheaper proof verification - but the math behind how they work is considerably more complex.

There is a class of semi-scalable system which only scalably verifies computation, while still requiring every node to verify all the data. This can be made quite effective by using a set of compression tricks to replace most data with computation. This is the realm of rollups.

Scalable verification of data availability is harder

A fraud proof cannot be used to verify availability of data. Fraud proofs for computation rely on the fact that the inputs to the computation are published on-chain the moment the original claim is submitted, and so if someone challenges, the challenge execution is happening in the exact same "environment" that the original execution was happening. In the case of checking data availability, you cannot do this, because the problem is precisely the fact that there is too much data to check to publish it on chain. Hence, a fraud proof scheme for data availability runs into a key problem: someone could claim "data X is available" without publishing it, wait to get challenged, and only then publish data X and make the challenger appear to the rest of the network to be incorrect.

This is expanded on in the fisherman's dilemma:

The core idea is that the two "worlds", one where V1 is an evil publisher and V2 is an honest challenger and the other where V1 is an honest publisher and V2 is an evil challenger, are indistinguishable to anyone who was not trying to download that particular piece of data at the time. And of course, in a scalable decentralized blockchain, each individual node can only hope to download a small portion of the data, so only a small portion of nodes would see anything about what went on except for the mere fact that there was a disagreement.

The fact that it is impossible to distinguish who was right and who was wrong makes it impossible to have a working fraud proof scheme for data availability.

Frequently asked question: so what if some data is unavailable? With a ZK-SNARK you can be sure everything is valid, and isn't that enough?

Unfortunately, mere validity is not sufficient to ensure a correctly running blockchain. This is because if the blockchain is valid but all the data is not available, then users have no way of updating the data that they need to generate proofs that any future block is valid. An attacker that generates a valid-but-unavailable block but then disappears can effectively stall the chain. Someone could also withhold a specific user's account data until the user pays a ransom, so the problem is not purely a liveness issue.

There are some strong information-theoretic arguments that this problem is fundamental, and there is no clever trick (eg. involving cryptographic accumulators) that can get around it. See this paper for details.

So, how do you check that 1 MB of data is available without actually trying to download it? That sounds impossible!

The key is a technology called data availability sampling. Data availability sampling works as follows:

Erasure codes transform a "check for 100% availability" (every single piece of data is available) problem into a "check for 50% availability" (at least half of the pieces are available) problem. Random sampling solves the 50% availability problem. If less than 50% of the data is available, then at least one of the checks will almost certainly fail, and if at least 50% of the data is available then, while some nodes may fail to recognize a block as available, it takes only one honest node to run the erasure code reconstruction procedure to bring back the remaining 50% of the block. And so, instead of needing to download 1 MB to check the availability of a 1 MB block, you need only download a few kilobytes. This makes it feasible to run data availability checking on every block. See this post for how this checking can be efficiently implemented with peer-to-peer subnets.

A ZK-SNARK can be used to verify that the erasure coding on a piece of data was done correctly, and then Merkle branches can be used to verify individual chunks. Alternatively, you can use polynomial commitments (eg. Kate (aka KZG) commitments), which essentially do erasure coding and proving individual elements and correctness verification all in one simple component - and that's what Ethereum sharding is using.

Recap: how are we ensuring everything is correct again?

Suppose that you have 100 blocks and you want to efficiently verify correctness for all of them without relying on committees. We need to do the following:

And that's all there is to it! In the case of Ethereum sharding, the near-term plan is to make sharded blocks data-only; that is, the shards are purely a "data availability engine", and it's the job of layer-2 rollups to use that secure data space, plus either fraud proofs or ZK-SNARKs, to implement high-throughput secure transaction processing capabilities. However, it's completely possible to create such a built-in system to add "native" high-throughput execution.

What are the key properties of sharded systems and what are the tradeoffs?

The key goal of sharding is to come as close as possible to replicating the most important security properties of traditional (non-sharded) blockchains but without the need for each node to personally verify each transaction.

Sharding comes quite close. In a traditional blockchain:

In a sharded blockchain with advanced security features:

Traditional high-TPS chains without sharding do not have a way of providing these guarantees. Multichain ecosystems do not have a way of avoiding the problem of an attacker selecting one chain for attack and easily taking it over (the chains could share security, but if this was done poorly it would turn into a de-facto traditional high-TPS chain with all its disadvantages, and if it was done well, it would just be a more complicated implementation of the above sharding techniques).

Sidechains are highly implementation-dependent, but they are typically vulnerable to either the weaknesses of traditional high-TPS chains (this is if they share miners/validators), or the weaknesses of multichain ecosystems (this is if they do not share miners/validators). Sharded chains avoid these issues.

However, there are some chinks in the sharded system's armor. Notably:

These are valid concerns, though in our view they are far outweighed by the reduction in user-level centralization enabled by allowing more applications to run on-chain instead of through centralized layer-2 services. That said, these concerns, especially the last two, are in practice the real constraint on increasing a sharded chain's throughput beyond a certain point. There is a limit to the quadraticness of quadratic sharding.

Incidentally, the growing safety risks of sharded blockchains if their throughput becomes too high are also the key reason why the effort to extend to super-quadratic sharding has been largely abandoned; it looks like keeping quadratic sharding just quadratic really is the happy medium.

Why not centralized production and sharded verification?

One alternative to sharding that gets often proposed is to have a chain that is structured like a centralized high-TPS chain, except it uses data availability sampling and sharding on top to allow verification of validity and availability.

This improves on centralized high-TPS chains as they exist today, but it's still considerably weaker than a sharded system. This is for a few reasons:

Properly sharded systems are better as a base layer. Given a sharded base layer, you can always create a centralized-production system (eg. because you want a high-throughput domain with synchronous composability for defi) layered on top by building it as a rollup. But if you have a base layer with a dependency on centralized block production, you cannot build a more-decentralized layer 2 on top.