The bulldozer vs vetocracy political axis

2021 Dec 19

See all posts

The bulldozer vs vetocracy political axis

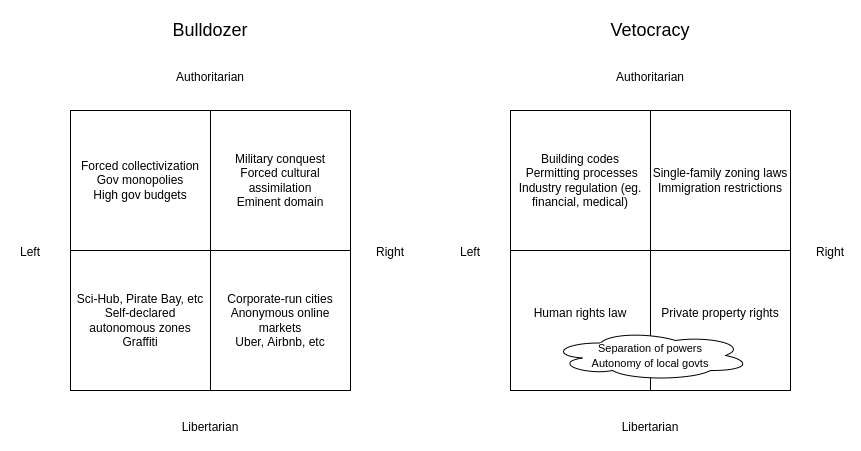

Typically, attempts to collapse down political preferences into a few

dimensions focus on two primary dimensions: "authoritarian vs

libertarian" and "left vs right". You've probably seen political

compasses like this:

There have been many variations on this, and even an entire subreddit

dedicated to memes based on these charts. I even made a spin on the

concept myself, with this

"meta-political compass" where at each point on the compass there is

a smaller compass depicting what the people at that point on the compass

see the axes of the compass as being.

Of course, "authoritarian vs libertarian" and "left vs right" are

both incredibly un-nuanced gross oversimplifications. But us

puny-brained human beings do not have the capacity to run anything close

to accurate simulations of humanity inside our heads, and so sometimes

incredibly un-nuanced gross oversimplifications are something we

need to understand the world. But what if there are other incredibly

un-nuanced gross oversimplifications worth exploring?

Enter the bulldozer vs

vetocracy divide

Let us consider a political axis defined by these two opposing

poles:

- Bulldozer: single actors can do important and

meaningful, but potentially risky and disruptive, things without asking

for permission

- Vetocracy: doing anything potentially disruptive

and controversial requires getting a sign-off from a large number of

different and diverse actors, any of whom could stop it

Note that this is not the same as either authoritarian vs libertarian

or left vs right. You can have vetocratic authoritarianism, the

bulldozer left, or any other combination. Here are a few examples:

The key difference between authoritarian bulldozer and authoritarian

vetocracy is this: is the government more likely to fail by doing

bad things or by preventing good things from happening?

Similarly for libertarian bulldozer vs vetocracy: are private actors

more likely to fail by doing bad things, or by standing in the way of

needed good things?

Sometimes, I hear people complaining that eg. the United States (but

other countries too) is falling behind because too many people use

freedom as an excuse to prevent needed reforms from happening. But is

the problem really freedom? Isn't, say, restrictive

housing policy preventing GDP from rising by 36% an example of the

problem precisely being people not having enough freedom to

build structures on their own land? Shifting the argument over to saying

that there is too much vetocracy, on the other hand, makes the

argument look much less confusing: individuals excessively blocking

governments and governments excessively blocking individuals are not

opposites, but rather two sides of the same coin.

And indeed, recently there has been a bunch of political writing

pointing the finger straight at vetocracy as a source of many huge

problems:

And on the other side of the coin, people are often confused when

politicians who normally do not respect human rights suddenly appear

very pro-freedom in their love of Bitcoin. Are they libertarian, or are

they authoritarian? In this framework, the answer is simple: they're

bulldozers, with all the benefits and risks that that side of the

spectrum brings.

What is vetocracy good for?

Though the change that cryptocurrency proponents seek to bring to the

world is often bulldozery, cryptocurrency governance internally is often

quite vetocratic. Bitcoin governance famously makes it very difficult to

make changes, and some core "constitutional norms" (eg. the 21 million

coin limit) are considered so inviolate that many Bitcoin users consider

a chain that violates that rule to be by-definition not Bitcoin,

regardless of how much support it has.

Ethereum protocol research is sometimes bulldozery in

operation, but the Ethereum EIP process that governs the final

stage of turning a research proposal into something that actually makes

it into the blockchain includes a fair

share of vetocracy, though still less than Bitcoin. Governance over

irregular state changes, hard forks that interfere with the

operation of specific applications on-chain, is even more vetocratic:

after the DAO fork, not a single proposal to intentionally "fix" some

application by altering its code or moving its balance has been

successful.

The case for vetocracy in these contexts is clear: it gives people a

feeling of safety that the platform they build or invest on is not going

to suddenly change the rules on them one day and destroy everything

they've put years of their time or money into. Cryptocurrency proponents

often cite Citadel

interfering in Gamestop trading as an example of the opaque,

centralized (and bulldozery) manipulation that they are fighting

against. Web2 developers often complain

about centralized platforms suddenly

changing their APIs in ways that destroy startups built around their

platforms. And, of course....

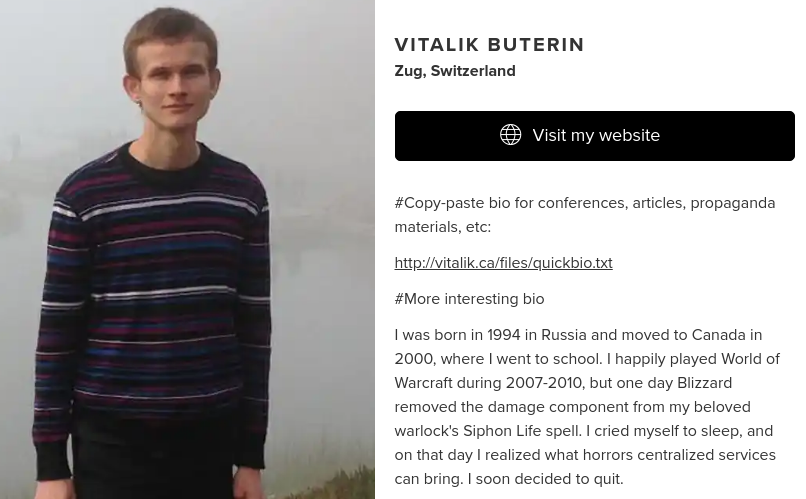

Vitalik Buterin, bulldozer victim

Ok fine, the story that WoW removing Siphon Life was the direct

inspiration to Ethereum is exaggerated, but the infamous patch that

ruined my beloved warlock and my response to it were very real!

And similarly, the case for vetocracy in politics is clear: it's a

response to the often ruinous excesses of the bulldozers, both relatively minor

and unthinkably

severe, of the

early 20th century.

So what's the synthesis?

The primary purpose of this point is to outline an axis, not to argue

for a particular position. And if the vetocracy vs bulldozer axis is

anything like the libertarian vs authoritarian axis, it's inevitably

going to have internal subtleties and contradictions: much like a free

society will see people voluntarily joining internally autocratic

corporations (yes, even lots of people who are totally not economically

desperate make such choices), many movements will be vetocratic

internally but bulldozery in their relationship with the outside

world.

But here are a few possible things that one could believe about

bulldozers and vetocracy:

- The physical world has too much vetocracy, but the digital world has

too many bulldozers, and there are no digital places that are truly

effective refuges from the bulldozers (hence: why we need

blockchains?)

- Processes that create durable change need to be bulldozery toward

the status quo but protecting that change requires a vetocracy. There's

some optimal rate at which such processes should happen; too much and

there's chaos, not enough and there's stagnation.

- A few key institutions should be protected by strong vetocracy, and

these institutions exist both to enable bulldozers needed to enact

positive change and to give people things they can depend on

that are not going to be brought down by bulldozers.

- In particular, blockchain base layers should be vetocratic, but

application-layer governance should leave more space for bulldozers

- Better economic mechanisms (quadratic voting? Harberger

taxes?) can get us many of the benefits of both vetocracy and

bulldozers without many of the costs.

Vetocracy vs bulldozer is a particularly useful axis to use when

thinking about non-governmental forms of human organization,

whether for-profit companies, non-profit organizations, blockchains, or

something else entirely. The relatively easier ability to exit from such

systems (compared to governments) confounds discussion of how

libertarian vs authoritarian they are, and so far blockchains and even

centralized tech platforms have not really found many ways to

differentiate themselves on the left vs right axis (though I would love

to see more attempts at left-leaning crypto projects!). The vetocracy vs

bulldozer axis, on the other hand, continues to map to non-governmental

structures quite well - potentially making it very relevant in

discussing these new kinds of non-governmental structures that are

becoming increasingly important.

The bulldozer vs vetocracy political axis

2021 Dec 19 See all postsTypically, attempts to collapse down political preferences into a few dimensions focus on two primary dimensions: "authoritarian vs libertarian" and "left vs right". You've probably seen political compasses like this:

There have been many variations on this, and even an entire subreddit dedicated to memes based on these charts. I even made a spin on the concept myself, with this "meta-political compass" where at each point on the compass there is a smaller compass depicting what the people at that point on the compass see the axes of the compass as being.

Of course, "authoritarian vs libertarian" and "left vs right" are both incredibly un-nuanced gross oversimplifications. But us puny-brained human beings do not have the capacity to run anything close to accurate simulations of humanity inside our heads, and so sometimes incredibly un-nuanced gross oversimplifications are something we need to understand the world. But what if there are other incredibly un-nuanced gross oversimplifications worth exploring?

Enter the bulldozer vs vetocracy divide

Let us consider a political axis defined by these two opposing poles:

Note that this is not the same as either authoritarian vs libertarian or left vs right. You can have vetocratic authoritarianism, the bulldozer left, or any other combination. Here are a few examples:

The key difference between authoritarian bulldozer and authoritarian vetocracy is this: is the government more likely to fail by doing bad things or by preventing good things from happening? Similarly for libertarian bulldozer vs vetocracy: are private actors more likely to fail by doing bad things, or by standing in the way of needed good things?

Sometimes, I hear people complaining that eg. the United States (but other countries too) is falling behind because too many people use freedom as an excuse to prevent needed reforms from happening. But is the problem really freedom? Isn't, say, restrictive housing policy preventing GDP from rising by 36% an example of the problem precisely being people not having enough freedom to build structures on their own land? Shifting the argument over to saying that there is too much vetocracy, on the other hand, makes the argument look much less confusing: individuals excessively blocking governments and governments excessively blocking individuals are not opposites, but rather two sides of the same coin.

And indeed, recently there has been a bunch of political writing pointing the finger straight at vetocracy as a source of many huge problems:

And on the other side of the coin, people are often confused when politicians who normally do not respect human rights suddenly appear very pro-freedom in their love of Bitcoin. Are they libertarian, or are they authoritarian? In this framework, the answer is simple: they're bulldozers, with all the benefits and risks that that side of the spectrum brings.

What is vetocracy good for?

Though the change that cryptocurrency proponents seek to bring to the world is often bulldozery, cryptocurrency governance internally is often quite vetocratic. Bitcoin governance famously makes it very difficult to make changes, and some core "constitutional norms" (eg. the 21 million coin limit) are considered so inviolate that many Bitcoin users consider a chain that violates that rule to be by-definition not Bitcoin, regardless of how much support it has.

Ethereum protocol research is sometimes bulldozery in operation, but the Ethereum EIP process that governs the final stage of turning a research proposal into something that actually makes it into the blockchain includes a fair share of vetocracy, though still less than Bitcoin. Governance over irregular state changes, hard forks that interfere with the operation of specific applications on-chain, is even more vetocratic: after the DAO fork, not a single proposal to intentionally "fix" some application by altering its code or moving its balance has been successful.

The case for vetocracy in these contexts is clear: it gives people a feeling of safety that the platform they build or invest on is not going to suddenly change the rules on them one day and destroy everything they've put years of their time or money into. Cryptocurrency proponents often cite Citadel interfering in Gamestop trading as an example of the opaque, centralized (and bulldozery) manipulation that they are fighting against. Web2 developers often complain about centralized platforms suddenly changing their APIs in ways that destroy startups built around their platforms. And, of course....

Vitalik Buterin, bulldozer victim

Ok fine, the story that WoW removing Siphon Life was the direct inspiration to Ethereum is exaggerated, but the infamous patch that ruined my beloved warlock and my response to it were very real!

And similarly, the case for vetocracy in politics is clear: it's a response to the often ruinous excesses of the bulldozers, both relatively minor and unthinkably severe, of the early 20th century.

So what's the synthesis?

The primary purpose of this point is to outline an axis, not to argue for a particular position. And if the vetocracy vs bulldozer axis is anything like the libertarian vs authoritarian axis, it's inevitably going to have internal subtleties and contradictions: much like a free society will see people voluntarily joining internally autocratic corporations (yes, even lots of people who are totally not economically desperate make such choices), many movements will be vetocratic internally but bulldozery in their relationship with the outside world.

But here are a few possible things that one could believe about bulldozers and vetocracy:

Vetocracy vs bulldozer is a particularly useful axis to use when thinking about non-governmental forms of human organization, whether for-profit companies, non-profit organizations, blockchains, or something else entirely. The relatively easier ability to exit from such systems (compared to governments) confounds discussion of how libertarian vs authoritarian they are, and so far blockchains and even centralized tech platforms have not really found many ways to differentiate themselves on the left vs right axis (though I would love to see more attempts at left-leaning crypto projects!). The vetocracy vs bulldozer axis, on the other hand, continues to map to non-governmental structures quite well - potentially making it very relevant in discussing these new kinds of non-governmental structures that are becoming increasingly important.